The doorman roused as the doorknob turned and someone walked in. In the blurry haze before he fully woke and put on his glasses he saw a form- a bit more portly than most that walked through those doors. Familiar? Perhaps, but not a regular.

"Be thee Met or be thee not? For only Met shall pass!" he declared while clambering around the desk for his glasses.

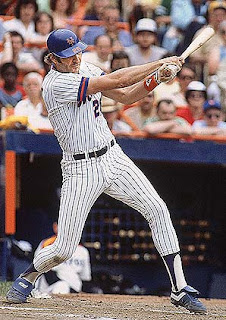

"Met? You betcha! Here, need proof?" The man produced a magnifying glass and held it up to his handlebar mustache. The doorman squinted forward, and yes, he believed he knew those follicles. His hand found his glasses, and now the mustache was magnified to the point that for a normally-sighted person it would be a sight reminiscent of a high-school science class.

"Keith, what are you doing here?"

"I want to personally welcome the new first baseman. Davis. Y'know, there's all kinds of whispers about the kid's potential."

"They're saying he could be the next-"

"John Olerud! I know!" said Keith, cutting him off. "Of course he needs to work on his footwork before we can really talk in those terms but-"

He was interrupted by the front door opening. Ike Davis was backing in, dragging a short leather couch.

"Let me help you with that," said Keith, jogging over to grab the other end.

"Thanks mister," said Ike. "You wouldn't believe what people leave out on the street! It's like a furniture store where everything is free, the quality varies greatly, and there are no employees!"

"Sounds like my kind of place!" said Keith, hitting the button for the elevator. Ike found this an odd comment, but he was happy that this man, with his confident air, was agreeing with him.

They managed to squeeze the both of them and the couch pushed vertically up against the wall into the elevator.

"Floor-" started Ike, but Keith had already hit the button for 29. Keith gave a smile, intended to interpret his now apparent familiarity with Ike into friendliness, but this expression, though practiced, was tinged with just enough smarminess to keep Ike off balance.

"Ike Davis," said Ike, extending his hand. This would establish a base to work with- something the man clearly already had- but the formality would make the situation a touch easier.

"I know," said Keith, shaking his hand. "I watch all your games. I believe you know me as well. I'm the guy people think of when they hear the words 'Mets First Baseman.'"

Ike's eyes widened. "Mr. Dave Kingman? Well this is an hon-"

"Kingman!? Do you know what that guy's average was?" said Keith, more pissed off than he intended.

"My dad said the most towering home run he ever gave up came off Kingman's bat," said Ike apologetically.

"Oh, he could whack 'em," Keith acknowledged with an asymmetrical smile.

The elevator opened into Ike's apartment. They carefully tipped the couch over and carried it in.

"Anywhere's good," said Ike. "We can just leave it here."

"Here? You'll cut the room in half! You need to think about where people will be and the angle they are most likely to face. Leave it here and your parties won't have any sense of community." Keith suggested and Ike agreed that the couch ought to be along the wall by the coffee table.

"Well, if you're an old Met, I bet you'd like a coconut!" said Ike, moving toward the refrigerator.

"Nah, we didn't really do that in my day. The coconuts- y'know, I mean, I guess management's really into 'em right now. There's always something. With us, if you got Davey mad during a game, he'd make you do a shot with him right there in the clubhouse."

Meanwhile, on the 20th floor, Howard Johnson, another former victim to Davey's odd punishment, had a bad feeling. He was writing poetry on the walls of his dwelling to try and get to the heart of it. This, as he told the lady in the scarlet dress that night she came over, is how he really knows what he's thinking.

It's like I've got an itch

but I don't know where it is.

I've got all this money,

but it won't buy me what I want,

which is a flying car.

HoJo thought about it. Yeah, he really did want a flying car. He had never articulated this desire to himself before, but now that he was envisioning the city whizzing by, the wind throttling his head, the thrill of the speed. Yeah...

He whacked off the top of a young coconut with a machete and got in the elevator to go take a walk. Perhaps when he was done with the coconut he would toss it into the Gowanus Canal and watch it float away.

"Afternoon, Pops," he said to the doorman as he crossed the lobby.

"Didja see your friend?" asked Pops, not looking up from his newspaper.

"Sure did, but only in my imagination. Her name was Violet. She was a flying car."

"No, the other guy." Howard looked at him puzzled. Pops passed his finger between his upper lip and nose to mime the full-bodied caterpillar of the last man to pass through. Johnson was so shocked he dropped his coconut, but caught it with his other hand.

"Still got those reflexes," admired Pops.

"Where is he?

"Helping Davis with some furniture."

"Oh no!" said Hojo, dashing for the elevator. "That's bitter sunlight for our brightest seed!"

The elevator wasn't as fast as some of the modern ones, but it got the job done. At this moment though, its deliberate speed frustrated Hojo to no end. In the brief trip from the first floor to the twenty-ninth, he found time to shout "GO GO GO!" The "goes" were heard, disembodied, by Angel Pagan, Gary Matthews Jr. and Jeff Francouer on their respective floors. Frenchy and Little Sarge were separately inspired to do nearly identical dances. Pagan happened to be flipping through a magazine and glancing at an ad for sessions in a floating tank. When he heard "GO!" he said, "Fine, I'll just do it. Will that make you happy?" There was no one there to answer his question, so he did it himself. "Perhaps it will."

As the elevator arrived at Ike Davis' apartment, Hojo could hear his old teammate's voice.

"But you can't cross your legs up like this or you'll end up like, like-"

"Like a cross-eyed ballerina!" offered Ike.

"I like you kid," said Keith. They were bent over in anticipation of imagined ground balls.

"HoJo! Great to see you buddy. I was just showing the kid some things here. I've noticed he gets a little crossed up sometimes."

"This ain't your place Keith," said HoJo, barely containing himself. You're not on the staff."

"Whoa, alright, I just have some knowledge that can help him out. You want to get these good habits started early."

"He's got great habits!" roared Johnson. "We don't need what you have to teach! We're doing something new here!"

"Something new? We were champions!"

"And what are we now?" Johnson was close enough to smell Keith's cologne. Desert Spice. He had worn the same one for twenty-four years. Keith's smell preference had been old enough to drink for three years. This thought hit HoJo like a fang, but the poison made him all the more righteous.

"Come on man, I was like Fred Astaire out there!" Keith went back down into his first baseman's crouch and mimed a diving grab, then taking it to the bag himself, working in an unnecessary spin move. "Hernandez gets them out of a jam again and you can PUT IT IN THE BOOKS!" he narrated.

"You just don't get it," said Johnson, brooding behind his coconut.

Keith shrugged. "I had a good time talking ball and social dynamics," he said to Ike. He got back in the elevator, which didn't seem overly slow to him. In fact it felt just right.

Of course, his ride was shorter than Johnson's had been because he hit the button for floor 17. The apartment he stepped into was full of plants, perching, sitting and hanging everywhere they could fit. Fernando Tatis was relaxing on a bean bag chair, an electric fan only inches from his face.

"Wow, there are so many more plants than when I used to live here."

"This is obvious," said Tatis.

"Say, you play some first, Fernando," Keith started.

"Also obvious," said Tatis, "and inconsequential."

"Inconsequential? Of course it's consequential! I'll show you inconsequential!" Keith gargled the first part of the William Tell overture. Tatis had to agree, this action was of no consequence. "There's a lot of tradition behind Mets first basemen."

"Tradition? There was you. There was me. There were others. All humans. Clever fools, just doing their jobs. Soon I will be gone, and there will be others who do my job. I am merely holding a place until another human occupies it. Plants have been around for many millions of years. That is tradition. That matters. Mets first basemen are plumbers with nothing to fix. I like Ike though."

"Yeah..." said Keith, scratching the back of his head, forgetting why he'd shown up. Then he remembered. "Hey, mind if I open up vent duct for a second?" Tatis made a casual assenting motion, and Keith walked over to a corner and pushed a potted plant to one side.

"Replace the plant when you are done," he said.

Keith took a Swiss army knife out of his pocket and pulled out the screwdriver (after mistakenly going for the saw first). He took the cover off the vent and reached his arm all the way in. Tatis had been barely regarding him up until now, but he sat forward to see what came out of the duct. It was a long, tinted bottle covered in dust, half-full of a murky blue liquid.

"I used to have this with Davey Johnson, our old manager. It'll, uh... heh, y'know..." Keith made a series of expressions to indicate that he didn't have the words to finish his sentence, but this was a powerful drink.

Seventeen seconds later, Keith was pouring small amounts of the liquid into two glasses. The two players clinked glasses and downed their swigs. It was as much a feeling as a taste that hit Fernando. It seemed to awaken every cell that it touched, setting off a harsh but beautiful cacophony of sensations. Keith flashed him a knowing smile.

"This," said Tatis, "this matters."

A coconut shell lay on Howard Johnson's floor.

An old coconut

has a handsome husk,

but no water.

Like a snake, I shed my skin.

And slither on the ground.

And swallow my food whole-

sometimes taking weeks to fully think it through.

You may find it grotesque.

But I call it living.

"Not bad," said the lady who lay supine on the sofa.

"Thanks for coming on such short notice," said Howard.

"Of course." She sipped wine the same color as her dress. "What's it about?"

"This is it," said Howard, defiantly. "This is how I'm expressing what's inside of me."

She considered this as she sat up, pushing her auburn hair out of her eyes. "If you had to distill it to one sentence. If you were in court and the judge said, 'Howard Johnson, bare your soul in one complete sentence,' how would you respond?"

Howard looked at the words he'd written on his wall, taking in each one, letting each one hit him. He picked up a piece of the young coconut off his floor.

"Sometimes I feel the weight of time, like three hundred boulders pushing on me from all sides." He held eye contact with the lady for a moment brimming with meaning. "Also, Keith Hernandez is a bastard."

Nine floors above. Ike Davis was dreaming. He saw a fork in the road. Down one way, Keith Hernandez was tap-dancing, magically fielding grounders from all sides. He would pick them and then toss them into the air, where they would explode into fireworks. Down the other fork was Jerry Manuel, Dan Warthen, and the rest of the coaching staff. They stood together, mostly still, as if posing for a picture. Howard Johnson held out a young coconut, open with a straw in it.

"I guess you could call us believers," he said, echoing the first thing he had said to Ike.

Behind Ike stood his backup, Fernando Tatis. He was drinking something strange and blue. "I know which way you will choose. And I also know it is inconsequential."

"Of course it's consequential," said Ike.

"All that matters," said an old, bald man appearing behind Tatis, "is that you bring down the military-industrial complex."

"Look dude," cried Ike. "I just got called up! I know people have a lot of expectations of me, but I'm just trying to stick around!"

"Right," said the old man. "Sorry."

Keith Hernandez launched one final ground ball into the air, and everyone, even the coaching staff, watched as it exploded in blue and orange glory before fading into ash in the sky.

"You must admit," said Tatis. "That guy is cool."